Braving the Stave

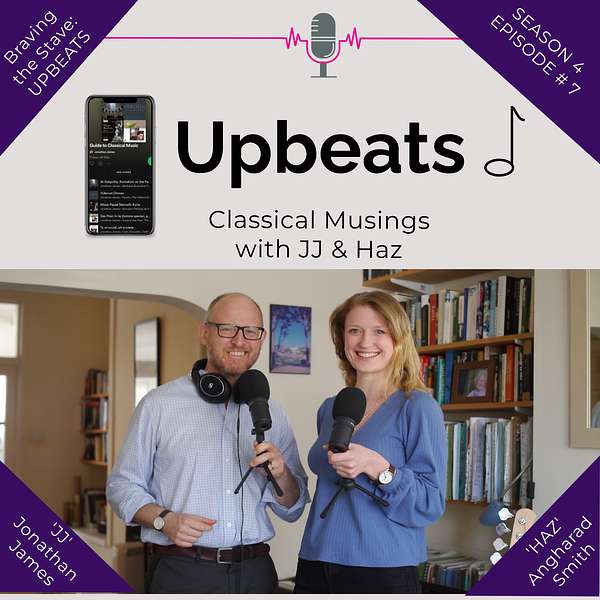

Hosted by Jonathan James and joined by Angharad Smith, a.k.a ‘JJ & Haz’ , this bubbly duo delve through all music and genres, sharing with you their personal favourite pieces, along with some musical jokes that add a playful and informal feel to the podcast. Working as part of Arts Active's Cardiff Classical programme, we run lots of exciting extras alongside it to support the concerts. Check out the Arts Active website for more - www.artsactive.org.uk

Got any comments for JJ and Haz? Email them to A2@artsactive.org.uk

--------------------------------------------------------

Yn cael eu cyflwyno gan Jonathan James, yng nghwmni Angharad Smith, neu ‘JJ a Haz’ fel y’u gelwir, mae’r ddeuawd fyrlymus hon yn pori drwy bob math o gerddoriaeth a genres, gan rannu gyda chi eu hoff ddarnau personol, ynghyd â rhai jôcs cerddorol sy’n ychwanegu teimlad chwareus ac anffurfiol i’r podlediad. Gan weithio fel rhan o'r rhaglen Gyfres Glasurol Actifyddion Artistig, rydym yn cynnal llawer o bethau ychwanegol cyffrous ochr yn ochr ag ef i gefnogi'r cyngherddau. Edrychwch ar wefan Arts Active i gael mwy - www.artsactive.org.uk

Oes gennych chi unrhyw sylwadau i JJ a Haz? Anfonwch ebost i A2@artsactive.org.uk

Braving the Stave

Upbeats: Season 4, Episode 7 (The Magic of Melody)

www.artsactive.org.uk

Email a2@artsactive.org.uk

X @artsactive

Instagram artsactivecardiff

Facebook artsactive

#classicalmusic #artsactive #drjonathanjames #bravingthestave #musicconversations #funfacts #guestspeakers #cardiff #cardiffclassical

Hello everyone, my name's JJ.

And my name's Haz.

And in this podcast, we're diving into the world of melody.

[ Harold Arlen: Over the Rainbow. Artists: Judy Garland]

Should we start with what melodies we can't get out of our heads?

A hundred percent.

Because 100 years ago. Germans called this an ohrwurm and it's stuck, so an 'earworm' and it's since been researched into and is a phenomenon And it's been called 'stuck tune syndrome' So this is the syndrome where you simply can't get that melody out of the head and it can be really distressing for some people because it becomes a psychological obsession, right?

Yeah.

Are you at that level?

Um, I am. I try and stay away from, you know, things like Instagram and TikTok, when you hear these songs on repeat, because now they use them as like little features and samples, it's kind of like stuck in my head all the time, like stupid little ditties, like that people sing to their dogs.

Okay.

Stuff like that. I hate it. And I get really cross at my ma'am if she sings them around the house. I'm like, ma'am, that's really, that's not cool. I've just got it out of my head.

Stop right there!

Yeah!

And I'm almost tempted to say, let's not sing or replay in any way any of our ohrwurms because you never know how triggering it could be to others. But like you, it tends for me to be a piece that I've just been rehearsing or working on. Um, And it will stay with me, uh, overnight, you know, I'll wake up thinking about it, humming it and over breakfast making porridge. There it is, you know, and then generally it fades. But I seem to remember you had a really good remedy for getting rid of earworms.

Oh God, what was it?

I think you said you would always sing a certain part of a certain piece and it would banish all earworms forever. Can you remember that?

I do not remember me saying that. That sounds like something I would say like black and white. Yeah, I believe in this and then completely forget it.

Ah, right. I thought it was something like, uh, the chorus of the Welsh national anthem.

I mean, that would be grand.

That would do it.

I would accept that.

Yeah, we could do that.

You can banish it. Yeah, that's it. You can banish it with your favorite tune. Just sing your favorite tune over and over in your head and it will get rid of that Happy Birthday chorus forever.

There we go. And so we have just righted a major national problem with Stuck Tune Syndrome. So there you go. Um, let's start off by just asking what makes for a bad melody?

Well, I've got no qualifications in that at all, but I think something that is too repetitive, something that is too easily hummable, and therefore everyone can sing it, and, it's around constantly.

Okay, so you want something special that makes it unique and makes it stand out in some way.

Yeah.

That's interesting because some people would say, actually, um, what I want from a melody is for it to be memorable.

Yeah, I mean, there's a reason that Christmas carols, we can all sing those, like Jingle Bells isn't that taxing, We Wish You A Merry Christmas isn't that hard, but I guess In the Bleak Mid... I don't know actually.

You're going Christmasy.

Sorry, yeah, I know, let me think, okay.

It's March Haz!

You Are My Sunshine, You Are My Sunshine, that's a good one, that's a happy one, right?

Yeah

Everyone seems to remember that. I suppose it's easily singable, easily hummable.

You're worried about it getting hackneyed.

Yes.

And routine.

Yes.

You want your melodies to be special.

Yeah.

Okay. So I'm going to put forward the thought that, I mean, actually, I'm just a regurgitating here a TED talk about this very matter, the world's ugliest music, right? And we're about to play. So, you know, prepare yourselves, get, get your fingers stopped in your ears if necessary .

Oh no!

Because it's music without any discernible oral pattern. So there's no repetition of pitch, of register. There's nothing to anchor the ear in anything. So it is the sheer absence of melody and of anything else for that matter. Let's just have a quick listen.

[ Music]

Haz was just clicking her pen in sheer annoyance throughout that.

I'm just cross. Why would you write that? I mean, it doesn't...

To make a point.

Yeah, but it doesn't shock me. It just irks me.

So everything about that was unpredictable, including those rests. And so if you were to look at it, some fool has actually tried to put this onto paper and it's the most bizarre set of time signatures. And, uh, I don't know how they did it, but, um, it was actually developed to, I think, improve a sonar system. And so it had a scientific use, if not a musical one.

Oh, it's a load of rubbish. I just think... sorry to... who's that composer by the way?

We 're definitely not mentioning him now!

It's just like going into art gallery, you know, when they have like blank canvases and they're like, they just haven't hung anything there yet and people just stand there for ages like, "wow, that really does say something." and you're like, "no, it doesn't. Shut up. No, it doesn't. It says nothing. It's boring."

There's the emperor's new clothes coming on through.

Yeah!

Well, we won't get into the wider conversation around contemporary art. But what we can say is the opposite, then, is true, uh, what makes a good melody has to be some form of repetition and pattern that, uh, our ear can correspond to and, and feel reassured by. Some sense of being led through. Haz this is nodding profoundly.

Yes! Go on! Let's hear a tune, please!

Yeah, but you want to be... I'm gonna use the J word, you know, led on an emotional journey.

Yeah, right.

Yeah, right. There it is And so that I think implies some sense of dynamic flow, of dynamic interest, um, and obvious shaping, a sense of space, um, a sense of phrasing that we can lock onto. All these things feed into what makes a melody satisfying, you know, we want to be led to a climax.

And resolve.

And resolve.

Yeah.

Absolutely.

Because I think even if I sang this now, I reckon listeners will be able to finish it. So if I go [sings start of familiar tune]...

Oh yeah. There we go.

Exactly. You have to go [sings end of tune] at the end, otherwise you're a terrible person, I suppose, but, but yeah, it doesn't even have to be long. Just take us somewhere. We know how it finishes. Boom, done.

Did you know that Mozart's little nephews went up onto his piano, onto his fortepiano and went " ba ba ba ba ba ba bee..." .

And I'd strike them from the will.

That's it, that's gone, forever forgotten.

Drop kick that nephew, boom, out the window.

So of course he had to go " bee

Yeah, you have to.

You have to, don't you? So we want that from a good melody, we want that sense of expectation, set up and then to deliver on it. I think a good archetype for this is Tchaikovsky horn solo from his fifth symphony, it's from the slow movement, and I think listeners will be able to hear immediately, you know, a repetition of the phrase and how it goes up one, and you've got two shorter phrases answered by a longer one.

It's deeply satisfying. But let's just have an ear to the structure of this.[ [Tchaikovsky: Fifth Symphony , Slow Movement]

Isn't that satisfying?

Yeah, and you can... I feel like you know where it's going and you're like, "Oh, I can see the pattern here." And it's beautiful. I think that's lovely.

It's as reassuring as a hot mug of tea, said he, cradling a hot mug of tea.

Yeah, it really is.

Listeners, we're really relaxed here. Haz has actually turned up in her driving slippers.

And leg warmers.

And leg warmers.

That I, I honestly dropped so many hints to my godmother about these. I was like, "oh, those are lovely leg warmers. That would look amazing on me and that I would enjoy."

It's a bit of Welsh hygge

Thank you auntie Denise. So yeah, just sat here. That's what a good tune is. It makes you feel at home. It makes you feel like... yeah home and yeah, hygge.

Or it can excite you in some way, can't it? Let's just think of Classical music's best tunesmiths. Who would you go for?

Well, I've made a list.

OK.

Now, I've got a list of my favorites and you've started with absolute, my ride or die, it's Tchaikovsky, number one. You got Swan Lake. You got The Nutcracker. You've got Tchaik 5, which we just played already. You got the 1812. He was just this absolute hero at just pumping out these tunes.

Banging tunes.

Just tune after tune after... like number one after number one. And I think the only person we have the modern day equivalent of that is like John Williams. Tune after tune after tune.

He is pretty good at that.

Perfect at that and I just think, yeah, that makes me, I think, old-fashioned in a way that I like to know how it starts how it ends and, yeah, just a nice little resolution.

The Russians, generally the romantic Russians, we look to them from Glinka onwards

yeah,

and think yeah, there are lots of brilliantly crafted melodies there that have Uh, a folk style, uh, simplicity to them and accessibility to them. Um, but then given, often this symphonic reach.

But if they're folk songs, I suppose they've been passed down orally, haven't they? By ear and, and just sitting around and enjoying a cup of, I dunno, vodka! Are we generalizing?

Could be!

Um, yeah. And then, yeah, so I can understand why those melodies do last. So you've got Shostakovich.

Yes.

Is he Russian? I mean...

He definitely is.

But we look at you like, "yeah??!"

I mean, Soviet initially, right .

Okay. Um, we've also said... have we said Rachmaninoff yet?

We haven't, but you know, we can't talk about melody without referencing Rachmaninoff.

The OG.

Shall we at this stage just insert a lovely melody by Rachmaninoff?

Please, I'm going to get comfortable. But play the whole thing. Whatever you're going to play. Play the entirety of it. Go for it.

I think this should be your choice. What do you want?

Oh, well, actually, actually, I went to the best concert I've been to in so long the other day.

Wonderful.

This isn't even a plug, BBC Now were playing in the Brangwyn Hall.

Is that the National Orchestra of Wales, BBC Now?

Oh, it is, JJ, well done. Um, I've never been there as, uh, an audience member seeing a symphony orchestra, you know, like...

Have you not?

No. The acoustics are amazing.

I love Brangwyn.

Yeah. I've only ever played there being really nervous, or just sat there watching a school concert which has been dire. But, do you know what? This was beautiful, it was the best rendition I've ever heard and it was...

Wow.

Yeah, honestly, I cried from the beginning to the end and I usually only cry in the third movement. This is of course...

You save it for the third.

I know, yeah, it's Rach 2.

Right, and we're talking about symphony number two, not piano concerto number two.

Oh sorry, yeah, of course, obviously, there's only one Rach 2 in my head but for you, you think of the piano first, right?

Well I only bring up the piano concertos because if you think of the second and the third ones in particular, they're just crammed full of these big-boned Russian tunes, aren't they?

Yeah, he really could write 'em. He really could.

But let's listen to the one that you're thinking of from the second symphony. So which movement is this?

I could pick any of the movements, obviously, and I was humming the fourth one on the way here, but I'm going to go for the third movement.

This is the Adagio.

[ Rachmaninoff Second Symphony, 3rd movt. Adagio]

Fortunately, I did not cry today sitting next to you.

I don't know how to take that, Haz.

Take it as you will, JJ. But, uh, I cried all the way through the concert, but today, yeah.

You're all cried out, is what you're saying.

That's it.

That's what I'm hearing.

Emotionally spent.

Well, I can see why. I mean, it's romantic with a capital R, isn't it? I mean, it's just, uh, these overwhelmingly powerful surging strings that Rachmaninoff excelled in.

Yeah.

And it's the length of line that we associate with Rachmaninoff as well, isn't it?

That's it. And just a crackin' tune.

Can we dive deeper, I think, into the magic of melody?

Oh, let's plunge.

I feel that should be the title of this podcast - 'The Magic of Melody'.

That's good.

Should we do that?

Yeah, yeah, go on!

Okay. So I think you can look first of all at the use of nice wide intervals to get us out of just scales um, but that said, that said I'm going to start with a simple scale and so here's Fauré's Élégie, which is a lament, and as you might expect, it's made up principally of a descending scale, and this is just to prove that you can get away, if you're Fauré, you can get away with just a bell tolling on the piano and this lamenting falling scale.

[ Fauré: Élégie. Artists: Pierre Fontenelle, Marie

So that was Pierre Fontenelle accompanied by Marie, I want to say Datcharry.

Then say it.

Okay. Beautiful tone there.

Really gorgeous and I see what you mean about the simplicity of the scale. You don't think about it when you're listening to it because it sounds so complex with all the beautiful vibrato in the way that they play it but I suppose it is, oh it sounds rude to say simple... does it?!

Its power is in its simplicity and its eloquence is in the fact that it's just this forming motif that will come back in various different forms later. But here's an example, I suppose, of something that goes up and up and naturally our ear locks on to melodies that ascend, particularly if you've got ever widening intervals and the jumps get larger. Now this I know you'll love. This is Jeremy Brett singing on the 1964 recording of My Fair Lady by Lerner and Loewe On The Street Where You Live.

I love this tune so much.

Let's whistle along.

Lerner and Loewe: On The Street Where You Live from My Fair Lady. Artists: Jeremy Brett]

Yeah, I mean, I'm lost as a viola player. I need to be on the stage singing this. [sings] And then the last one. [sings]

That's a very impressive, uh, old era tenor sound that you're coming up with.

Honestly, we play this so often, as a duo, me and my sister at weddings where they're like, "can we have, um, really classic, you know, like R&B." And then I'm like, "nope." And we always stay On The Street Where You Live just because it's so good.

How can you not?

Yeah.

And it is about the melodies, isn't it? As well as the lovely moment within the film that it represents, you know, the nostalgia that goes with that. Sure. But yeah, as you said, you, you've got that such... it's such a satisfying peak, isn't it?

Yeah. That's it. And then it resolves at the end. "Do, do, do, do, do ,do, do, do, do, bom, bom, bom,

End . Cool.

Okay. Close.

Yes. Job done.

Yeah.

Well, I wanted to just look at how our ears can just lock on to repetition, even if you don't have the beauty of a melody like that. Here is, uh, Giant Steps, a, um, I know... I think you know this quite well, don't you?

I think I do.

Yes. Yes. Okay. So this is a Coltrane classic. So, um, within the bebop world, this is seen as getting your black belt, isn't it?

Yeah.

If you can do giant steps, then, and particularly if you can improvise over these chord changes, which are very fast moving, then you've kind of got access to the inner sanctum of bebop, haven't you?

Right. So let's dim the lights, get ourselves a whiskey, light a cigar.

Put on appropriate headwear and nod along to this. Now I think this will impress you. It's being sung, actually, unusually by Camille Bertault and she is this French singer who is brilliant at, well, just this fast diction and she has actually transcribed Coltrane's solo and set it to words.

Is it like a vocalise? Is that what you call it? Or something?

She's actually put lyrics to it.

Oh, cool.

In French, which is even cooler, obviously, to our ears.

Mais oui

So let's have a listen. Now, the main point is, if you listen to this opening phrase long enough, and to how it's repeated, it does lock on and you can end up whistling it afterwards is my contention.

Okay, here's the challenge.

[ John Coltrane: Giant Steps. Artist: Camille Bertault]

That's impressive.

Yeah, it really is. I think it helps that she's got such a beautiful voice because if you went around the supermarket singing that [ sings 'scat']

Probably annoy your fellow shoppers quite a bit.

You'd get sectioned. It's, it's like, I don't think you'd sound like a normal person, but she makes it sound really cool.

It's such a beautiful perfume, her voice, isn't it? Just floats around in a very French way.

Yeah, but I think the first bit [sings] You can definitely sing it.

I knew you could sing it, I was gonna challenge you and you've done it.

Well, I am an artiste! But the rest of it then I don't know if I could you kind of tail off and then wait for the head to come back and you're like, oh, yeah [ sings].

That's right. So all the, scatting almost, but with words in the middle is very impressive, but slightly puts me on edge and makes me a bit anxious, even with her beautiful voice.

Yeah.

The main point being that, yeah, we can hear that angular melody and lock onto it purely by virtue of repetition. Here's another thought.

One of the most beautiful things in melody is to aim for a note and then just pause on the note above and combine that with a lush chord beneath and you get an appoggiatura- a leaning note, right?

Mm-Hmm.

And so,[ sings], I dunno. My voice isn't great, is it?

No. I love your voice, JJ. Don't you say that about my friend

But that 'tee dah' you see I'm being emboldened now, is part of the romantic language of the melody.

Yeah.

To have these leaning notes. And it made me think of Bruch's Violin Concerto No. 1. He did do two. Did he do three actually?

I've no idea. My dude. I don't know. I've mimed so much orchestral music at this point that I can't remember which ones I've mimed.

Well, much to Bruch's dismay, it's the first violin concerto that we all know and love him for. And, uh, this is from the slow movement and just listen out to how many leaning notes there are in the tune. And this is played by Ray Chen and is rather beautiful.

[ Max Bruch: Violin Concerto No. 1, Slow Movement. Artists: Ray Chen]

Gosh, that was slow, wasn't it?

Yeah. Beautiful.

I mean, he is milking it somewhat.

Yeah.

But as you say, he's giving it the space that that movement requires. And did you hear the leaning notes there?

I did.

Oh, good.

I think we're just smiling because we were trying to think of a piece that we could play out our podcast, something that we both love, a tune that's so well loved, we both love. And we actually just spent the entirety of that.

Swearing.

Yeah!

We were swearing. At Melodies.

Things we hate. Jupiter. What do you say? Salut d'Amore.

Can't stand it.

Can't do it. Meditation. Won't have it.

The Thaïs. It's tricky.

Not doing it. Blue Danube.

Oh, definitely not.

Won't have it. What else? Oh, I wrote Gabriel's Oboe.

Yeah, I can see where it can be a bit wheedling. The trouble is I've heard too many poor performances.

"

Meh meh wah wah wah"

Exactly.

Awful.

Gabriel's cat!

And "Nella Fantasia..." Shut up. It doesn't make it any better that it's not an oboe. It's the same tune.

Oh, are you talking about the, the tenor version?

Oh, yeah, I hate it. Have we settled on one that we both love though?

I think so. Having just, you know, got that out of our system.

Just swearing for ten minutes about things we hate.

I think let's go to West Side Story to see us out.

Nailed it.

You can't go wrong with West Side Story.

Genuinely, yeah.

Generally speaking. And, well, which one would you like?

Well, [ sings: There's a Place...], but let's sing it as a duet. No, no, no, let's just play it!

Better not go there. I'm thinking of my own singing voice, of course, not yours.

Rude.

But, uh, we have actually played, uh, there's a place for us before in our vast back catalogue of podcasts, which can be found on multiple platforms. But also, can I just point out before I forget that we have a playlist called Braving the Stave on Spotify.

Well remembered. Very good.

Thank goodness. Thank goodness. So yes, and this particular song is based on the Tchaikovsky Romeo and Juliet cello tune and it opens with that same "da dee...", you know, that same...

I did not know that.

[sings] So, and he was, yeah, nodding towards Tchaikovsky in coming up with this absolutely beautiful tune.

So, Here it is. And with this, we say a very warm and cheery goodbye. I hope you agree with our melodies. If not, let us know and we'll be discussing harmony next time, which is a whole new world altogether.

Which is... Leave it to me. This is my forte now.

Great. I think you can take the lead. Great.

Oh, God!

Hwyl am y tro.

See you soon.

[ Leonard Bernstein: Somewhere from West Side Story.]